單元一:社會資本理論介紹

什麼是社會資本?

社會資本的背景

「社會資本」是過去二十年全球各地備受關注的概念,亦廣受不同界別政策制定者、學者及實踐者討論及應用,當中包括:社會學 (e.g., Portes, 1998; Walters, 2002)、經濟學 (e.g., Dasgupta, 2005; Glaeser et al., 2002)、公共衛生 (e.g., Kawachi et al., 2008; Villalonga-Olives et al., 2018)、社會服務 (e.g., Castillo de Mesa et al., 2019) 及社區發展 (e.g., Halstead et al., 2022; Williams et al., 2022) 等。在1990年代,美國學者羅伯特‧普特南 (Robert D. Putnam, 1995; 2000) 先後出版名為《獨自打保齡球》(Bowling Alone) 的書籍及相關文章,當中提及當時社會資本下降的現象,形容人們逐漸減少參與社交活動,人與人之間關係逐漸疏離及失去互信,以致出現社會孤立的處境,各種生活困難及社區問題也隨之衍生。在此之後,各界對社會資本的討論便更熱烈。不同國際組織包括:世界銀行 (World Bank)、聯合國 (United Nations) 及經濟合作暨發展組織 (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD) 均強調社會資本的重要性,尤其是在消除貧窮、社會持續發展及經濟發展等議題中擔當非常重要的角色 (Grootaert, 1998; United Nations Development Programme, 2009; Woolcock, 2001)。

不同的國際研究均指出社會資本為促進人們的身心健康 (Villalonga-Olives et al., 2018)、社區福祉 (Greenberg et al., 2016)、社會及經濟發展 (Wallis et al., 2004)、減輕貧困 (Zhang et al., 2017)、抵抗災禍 (Rapeli, 2018)、環境保護 (Su et al., 2021) 及種族共融 (Hawes & Rocha, 2011) 等,帶來正面的作用。而在過去的新冠疫情期間,多項研究亦指出社會資本有效協助社區共同抗疫,如防疫資訊的交流、各項保護措施的實施、維持社交距離,以及疫後的恢復 (e.g., Borgonovi & Andrieu, 2020; Pitas & Ehmer, 2020)。因此,世界各地政府及非政府組織均將發展社會資本作為重要的政策目標及實踐策略,希望為社會帶來長期和持續的影響。基金推動本港社會資本的發展如下圖(圖一)。

圖一:社會資本發展的目標

社會資本的定義

綜觀不同的國際文獻及研究,儘管學術界並未就社會資本提出劃一的定義,某些定義已經被廣泛引用。當中包括皮埃爾‧布迪厄 (Pierre Bourdieu)、詹姆斯‧科爾曼 (James Coleman)、羅伯特‧普特南 (Robert Putnam) 及林南 (Nan Lin) 所提出的定義(見下列社會資本主要理論部分)。根據世界銀行、不同學術研究結果及基金的計劃推行經驗,社會資本是指一些能夠有效促進社會互動質素和頻率的制度、關係和規範。社會資本亦包括社會規範(個人態度及社會價值觀)、網絡和制度(圖二)。

圖二:社會資本的定義

社會資本主要理論

在學術界中,著名的社會資本理論學者主要包括皮埃爾‧布迪厄 (Pierre Bourdieu)、詹姆斯‧科爾曼 (James Coleman) 、羅伯特‧普特南 (Robert Putnam) 及林南 (Nan Lin)。當中,皮埃爾‧布迪厄、詹姆斯‧科爾曼及林南的研究範圍主要集中在個人層面的社會資本,而羅伯特‧普特南則從社會層面出發。但四位學者的理論均提及個人層面與社會層面之間的相互影響。

皮埃爾·布迪厄 (Pierre Bourdieu) 的理論:資本理論 (Theory of Capital)

皮埃爾·布迪厄 (Bourdieu, 1977, 1986, 1990) 的主要研究範疇是有關社會階級、地位及權力關係的再生產 (Reproduction),當中涉及三項不同形式的資本,包括經濟、文化及社會資本。在布迪厄看來,階級再生產不僅可以用經濟學來解釋,亦可以透過社會階級互動關係(即社會資本)及文化知識(即文化資本)的傳承過程來分析闡明 (Bourdieu, 1986; Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992)。

根據布迪厄的說法,社會資本是實際或潛在資源的集合體,這些資源與人們對共同制度的熟悉程度和認可的關係網絡密切相關(Bourdieu, 1986, p. 249)。布迪厄指出個人所擁有的社會資本數量取決於他能有效動員的網絡連繫的規模和所擁有的經濟或文化資本 (Bourdieu, 1986)。布迪厄 (Bourdieu, 1984) 亦指出,文化資本在不同群體中有不同分佈,與階級差異直接有關。當中,布迪厄 (Bourdieu, 1977, 1986, 1990) 和克魯克 (Crook, 1997) 都表示教育可以影響文化實踐,通過正規及非正規(例如父母的教導)教育,不同階級人士獲得不同類型及層次的文化資本。例如:上大學的人可能有更多的機會學習古典音樂;支配階級能夠將其文化資本(例如高級舉止和生活方式)傳遞給子女等。通過此文化資本的傳遞,社會的階級關係(即社會資本)得以再生產,其經濟資本亦能得以維繫。

有些學者 (Alexander, 1996; Jenkins, 1992) 認為,布迪厄的理論是還原主義 (Reductionism),因為它把經濟資本視作所有其他資本的最終來源和交換形式。另外,戈德索普 (Goldthorpe, 1996) 亦指出布迪厄把人類所有行為都歸因於利益關係。施華茲 (Schuller, 2001, p. 12) 指出此導向是有局限性的,因為在這種導向下,所有社會資本的累積最終都會造成社會階級化與不平等。

詹姆斯·科爾曼 (James Coleman) 的理論:理性選擇 (Rational Choice)

科爾曼 (Coleman, 1988, 1990) 與布迪厄的理論相似,也將社會資本視為一種個人資產和集體資源。但與布迪厄不同的是,科爾曼認為社會資本是一種社會結構模式,並在特定環境中促進個體活動,從而獲得利益 (Coleman, 1990)。而人們為了能在活動中獲利,便會透過彼此互動,進行資源交換和轉移。這些互動的社會關係便構成了社會資本的基礎。

此外,社會資本還具有生產性,即社會資本具有明確的工具性目的 (Instrumental purpose),個人可運用社會資本以達到特定的目的。因此,社會資本必然在社會出現,並嵌入於社會結構中。正如科爾曼所言,社會資本是指社會關係結構中的資源,包括人際關係和機構聯繫(例如家庭、學校、工作和社區環境)。人們通過這種互動的社會關係或網絡,來獲取各種政治、經濟信息及資源,以提高其社會經濟地位。因此,擁有愈多社會網絡的人,其社會及經濟地位亦愈高。但是,與布迪厄不同,科爾曼認為社會資本是一種連結機制 (A bonding mechanism),讓不同的人連結在一起,用於社會結構的整合 (The integration of social structure) (Coleman, 1988, 1990)。

羅伯特·普特南 (Robert Putnam) 的社會資本理論:公民面向 (Civic Perspective)

普特南 (Putnam, 1993a, 1995, 2000) 採納了科爾曼提出的理論原則,並擴展到從政治學角度分析社會層面的社會資本。在他看來,社會資本指的是「社會組織的特徵,例如網絡、規範和信任,它們有助於人們採取行動與合作,以實現互惠互利」 (Putnam, 1993a, p. 35)。普特南認為,社會資本是一種可以促進人際合作的元素,並以民主社會的自願組織 (Voluntary associations) 作為例子說明其觀點的應用。他認為,自願組織是一種公民參與 (Civil engagement) ,而這種參與能促進及增強群體內人與人之間的規範和信任,最終產生和維持集體福祉(Collective well-being) (Putnam, 1993a, 1995)。

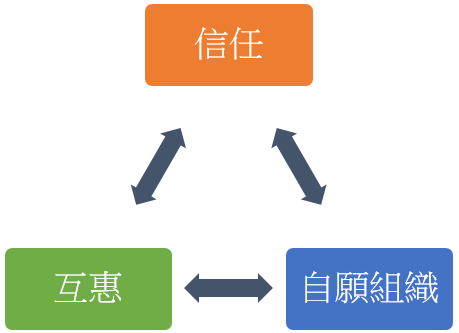

根據普特南的論點,自願組織促進人與人之間的橫向聯繫,並產生信任。這種信任帶來了互惠 (Reciprocity)、社會網絡 (Social networks) 和自願組織的發展,亦奠定了社會資本的基礎。當中,信任、互惠和自願組織之間存在一個循環:信任產生互惠和自願組織;而互惠和自願組織的加強亦會產生信任 (Putnam 1993b, pp. 163-185)(圖三)。同時,普特南特別將信任及其伴隨的互惠與公民參與聯繫起來,以此作為公民社會力量的指標 (As an index of the strength of civil society)。簡而言之,社會資本與社會參與(特別是通過參與自願組織)有著密切的關係。因此,普特南認為,社會資本是對公民力量的直接評估,並且可以成為反映社會、政治和經濟繁榮的工具 (Putnam, 1993a, 1995, 2000)。但是,一些學者 (Portes, 1998; Brucker, 1999; Foley & Edwards, 1999; Swain, 2003) 認為,普特南並未有準確及清晰地分析社會資本與社會、政治和經濟繁榮之間的因果關係。此外,普特南亦未有討論不同政黨和自願組織之間的衝突和內部權力結構,以及公民社會與政治社會(以及國家)之間的矛盾 (Siisiäinen, 2000)。

圖三:信任、互惠和自願組織之間循環

林南 (Nan Lin) 的社會資本理論:網絡導向 (Network Approach)

林南 (Lin, 2001a, 2001b) 的理論主要聚焦在關係性資產 (Relational assets), 他指出社會資本源自社會網絡及社會關係之內(圖四)。林南 (Lin, 2001b, p. 12) 指社會資本是「存在於社會結構中的資源,而這些資源能夠被使用及動員在特定目的的行動中」。林南的社會資本定義包含三種元素:(1)資源存在於社會結構中;(2)社會資源的可使用性;以及(3)應用在特定目的的行動中。林南進一步提出,有效運用社會網絡中的社會資源能夠提升社會及經濟地位;同時,社會資源的(部分)使用取決於社經地位及社會網絡的運用。

圖四:網絡導向的社會資本

有別於其他三位學者,林南將社會資本的討論延伸至開放性的社會網絡 (Open networks) (Lin, 2001a)。他指封閉性社會網絡 (Closed networks,又稱強連繫 Strong tie) 的有效性在於維持人們的資源與合作;而開放性社會網絡 (又稱弱連繫 Weak tie) 的用處則在於促進資源的增加及目的性行動的實踐 (Lin, 2008)。其後,林南 (Lin, 2008) 亦有提及集體層面的社會資本,指組群內的內部社會資本 (Internal Social Capital) 來自成員的資源提供,並有效維持組群的團結與凝聚;外部社會資本 (External Social Capital) 則指組群外部的資源及網絡,通過連結其他組群及組織來獲取,但其效能需要視乎跨組群之間的連繫及開放性。不過,亦有其他學者指出林南未有仔細探討運用社會資本改善社會不平等的可能性 (Häuberer, 2011)。

社會資本範疇

不同學者均傾向共識社會資本是涵蓋多維度範疇的 (Multidimensional) 概念,但所涵蓋的範疇仍未達成共識。而社會資本的範疇則基於不同的處境、視點及分析層面有不同的詮釋 (Woolcock & Narayan, 2000)。例如,普特南聚焦於網絡、規範及信任等範疇 (Putnam, 1993a);而林南則強調資源與社會網絡的重要性 (Lin, 2001a)。

社會資本六大範疇

根據世界銀行 (Grootaert et al., 2004, p. 5),社會資本包括六大範疇(圖五)︰(1)社會網絡;(2)信任和團結;(3)互助和互惠;(4)社會凝聚和包容;(5)社會參與;及(6)資訊和溝通。

圖五︰社會資本六大範疇

- 社會網絡 — 這是較普遍的社會資本範疇,指人們可接觸或參與的社會組織或非正規網絡;人們可從社會網絡中得益,亦可為其他社會網絡成員付出。

- 信任和團結 — 這是有關人們之間和對社會其他組群的信任。例如對鄰居、服務提供者及陌生人的信任程度。

- 互助和互惠 — 此範疇是指人們之間的互相幫助、共同合作以達到互惠互利。例如共同改善社區或回應社區的突發情況。

- 社會凝聚和包容 — 社區包括不同組群,而各組群的不同特徵及生活方式容易產生矛盾。此範疇是有關識別社區各組群的不同,增加彼此互動,並達致凝聚及互相包容。

- 社會參與 — 此範疇是指人們對社會組織或網絡的參與。例如通過參與自願或義務組織,服務社區內其他有需要的組群;與其他社區成員合作,共同改善社區問題。

- 資訊和溝通 — 這是有關資訊的傳遞及溝通渠道。例如人們如何獲得有關公共服務和資源的重要社區資訊,以及他們如何通過一些溝通渠道發表意見。

社會資本的類別及層面

凝聚型、搭橋型及連結型社會資本 (Bonding, Bridging and Linking Social Capital) (圖表一)

凝聚型社會資本 (Bonding Social Capital) 是群體內部現象,該群體是由背景相近的人士緊密地凝聚在一起而組成——這可從該群體的同質性、牢固的行為規範、忠誠度及排外性中反映出來(圖六)。其中一個典型的例子,是由一小撮緊密連繫而需要互相支持的新移民家庭所組成的群體 (Onyx & Bullen, 2001; Putnam, 2000)。

圖表一:凝聚型、搭橋型及連結型社會資本

社會資本類別 |

凝聚型社會資本 |

搭橋型社會資本 |

連結型社會資本 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

性質 |

同質性的羣組、成員有緊密的接觸 |

異質性的羣組、成員聯繫相對疏遠 |

不同社會階層、地位的個體或組織之間的聯繫 |

例子 |

家人、相熟朋友 |

一般朋友、同事及不同社區人士 |

個體或社區組織與政府機構之間的合作 |

圖六︰凝聚型社會資本 (Bonding Social Capital)

搭橋型社會資本 (Bridging Social Capital) 是指向外面對及聯繫社會上不同羣組 (Putnam, 2000) 而產生的社會資本(圖七)。例如:與一般朋友、同事及不同種族文化人士的社會聯繫。

圖七︰搭橋型社會資本 (Bridging Social Capital)

連結型社會資本 (Linking Social Capital) 是指把社會上不同人士和群組與社會上具有權力及資源的人士和群組連結起來(圖八)。通過此連結,機構、社會,甚至國家內的文化、價值觀及制度可被改變 (Woolcock, 2001)。

圖八︰連結型社會資本 (Linking Social Capital)

結構性、關係性及認知性社會資本 (Structural, Relational and Cognitive Social Captial)(圖表二) 結構性社會資本 (Structural Social capital) 是指聯繫人和團體的關係、網絡、組織和機構 (Coleman, 1988)。結構性社會資本可以通過分析聯繫的疏密和網絡的大小來量度 (Bourdieu, 1986)。

關係性社會資本 (Relational Social capital) 是指不同人士之間的關係。關係強度 (Granovetter, 1973) 經常被用作量度單位(例如關係接觸的次數及時間、關係之間的互信互惠程度、關係之間的凝聚及包容能力等)。

認知性社會資本 (Cognitive Social capital) 涉及信念和看法。在社區層面上,可通過鄰里之間的信任度、互惠和公民身份(例如是否覺得自己是社會的一份子)來量度。在個人層面則可以通過對社區的感受來量度,例如對社區的信任感、互惠的氣氛及歸屬感 (Putnam, 2000; Uslaner, 2002)。

圖表二:構性、關係性及認知性社會資本

社會資本類別 |

結構性社會資本 |

關係性社會資本 |

認知性社會資本 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

性質 |

社會結構 |

關係的性質及質素 |

共同理解 |

特徵 |

|

|

|

資料來源:Claridge, 2018a, p. 2

微觀、中觀及宏觀社會資本 (Micro, Meso and Macro Levels of Social Capital)

綜合有關社會資本的文獻,社會資本理論的分析層面會視乎研究的視點而略有不同 (Claridge, 2018b)。例如部份學者的研究聚焦在個人層面的社會資本,而另一些學者的討論則集中在社區層面的社會資本。社會資本存在於不同層面的社會結構,包括個人、團體、機構、社區、族裔群組,以及政府機構。不同層面的社會資本會重疊,亦會相互影響。

有學者 (Claridge, 2018b) 建議將社會資本劃分為三種層面,包括微觀(個人)、中觀(團體或機構)及宏觀(社區或社會)層面(圖九)。這種分類有助理解社會資本概念的複雜性——它是存在於不同層面的社會結構及複雜的社會環境(見圖表三)。

圖九:社會資本的三種層面

圖表三:微觀、中觀及宏觀社會資本

社會資本層面 |

內容 |

屬性 |

|---|---|---|

微觀 |

個人 |

|

中觀 |

團體或機構 |

|

宏觀 |

社區或社會 |

|

資料來源:Claridge, 2018b, p. 4

社會資本的關鍵因素 (Determinants of Social Capital)

了解及研究社會資本的關鍵因素是學術界及社會政策的重要議題,有助於制定社會資本發展實踐策略及政策 (Hanibuchi & Nakaya, 2013)。社會資本的關鍵因素是指有助促進社會互動合作,社會互助文化及規範的發展,以及信任、信念及價值建立等的重要因素 (Claridge, 2019)。雖然社會資本的關鍵因素所牽涉的內容非常廣泛並涉及不同層面的分析,不同學者亦嘗試整理及歸納不同研究的相近內容 (Claridge, 2019; Hanibuchi & Nakaya, 2013; Kaasa, 2019)。例如Claridge (2019, p. 1) 嘗試列出不同社會資本的因素,包括微觀及宏觀層面,如個人教育及家庭背景、鄰里環境、歷史及文化等(見圖表四)。另一些學者則嘗試將社會資本的關鍵因素分成個人及鄰里或環境關係層面 (Hanibuchi et al., 2012; Kaasa, 2019; Lindström et al., 2002)。

圖表四:社會資本的關鍵因素例子

社會資本層面 |

|

|---|---|

|

|

資料來源:Claridge, 2019, p. 1

個人層面的社會資本關鍵因素

不同研究指出一些個人層面的特徵或會影響社會資本的發展,如年齡、性別、教育程度、收入、婚姻及就業狀況等 (Kaasa & Parts, 2008)。個人的就業狀況是其中的重要因素,有研究指出面對失業的情況,人們會失去動力參與社區,甚至對社會發展失去信心 (Christoforou, 2005);此外,退休人士及家庭照顧者亦相對較少接觸正規的社會網絡 (van Oorschot et al., 2006)。

鄰里或環境關係層面的社會資本關鍵因素

有學者 (Hanibuchi & Nakaya, 2013) 指出了鄰里特徵及環境因素對於社會資本發展的影響 (Hanibuchi et al., 2012)。他們的研究聚焦於都市化的程度 (Urbanisation)、城市設計的可步行性 (Walkability) 及社區的歷史,藉此找出鄰里特徵與社會資本之間的關係。他們的研究發現,這些鄰里特徵或有助於居民建立信任感及歸屬感,參與社區組織,以及與朋友聯繫 (Hanibuchi et al., 2012)。

社會資本發展計劃的重要性

不同研究均指出社區發展性計劃有助於社會資本的建立,而發展社會資本亦有助達致不同社會成果 (Social outcomes),包括改善不同組群的健康、經濟情況及福祉。

社區計劃的社會資本成果

不同社區計劃的經驗均發現社會資本發展的成果,例如一些社區領袖發展計劃能夠有效發展居民建立社會網絡的能力,亦有助促進社會參與和社會組織及網絡的建立 (Burbaugh & Kaufman, 2017)。一些青年發展計劃及地區活動亦有助社會資本的發展,如促進建立社會信任、社區歸屬感,以及促進義務工作的參與 (Darcy et al., 2014; Krasny et al., 2015)。

福祉、健康及經濟成果

不同社區計劃亦透過促進社會資本發展,改善不同群組的福址、健康及經濟。例如透過發展社會資本營造年齡友善社區 (Age-friendly community),從而改善長者的精神健康 (Glicksman et al., 2016)。另外,社會資本發展亦能有效促進經濟發展 (Woolcock, 1998),如協助就業市場網絡的發展 (Asquith et al., 2021)、改善貧窮情況 (Halstead et al., 2022),以及推動社區經濟的發展 (Roxas & Azmat, 2014)。

參考資料

Alexander, C. E. (1996). The art of being black: The creation of black British youth identities. Clarendon Press.

Asquith, B., Hellerstein, J. K., Kutzbach, M. J., & Neumark, D. (2021). Social capital determinants and labor market networks. Journal of Regional Science, 61(1), 212-260.

Borgonovi, F., & Andrieu, E. (2020). Bowling together by bowling alone: Social capital and Covid-19. Social Science & Medicine, 265, 113501.

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste (R. Nice, Trans.). Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241-258). Greenwood Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice (R. Nice, Trans.). Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. J. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. University of Chicago Press.

Brucker, G. (1999). Civil traditions in premodern Italy. Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 29(3), 357-377.

Burbaugh, B., & Kaufman, E. K. (2017). An examination of the relationships between leadership development approaches, networking ability, and social capital outcomes. Journal of Leadership Education, 16(4), 20-39.

Castillo De Mesa, J., Gómez Jacinto, L., López Peláez, A., & Palma García, M. D. L. O. (2019). Building relationships on social networking sites from a social work approach. Journal of Social Work Practice, 33(2), 201-215.

Chan, C. W. (2018). The mental health of unemployed and socially isolated middle-aged men in Tin Shui Wai, Hong Kong (Doctoral dissertation, University of Essex). University of Essex Research Repository.

Christoforou, A. (2005). On the determinants of social capital in Greece compared to countries of the European Union. FEEM Working Paper 68.

Claridge, T. (2018a). Dimensions of social capital: Structural, cognitive, and relational. Social Capital Research, 1-4.

Claridge, T. (2018b). Explanation of the different levels of social capital: individual or collective?. Social Capital Research, 1-7.

Claridge, T. (2019). Sources of social capital. Social Capital Research, 1-9.

Claridge, T. (2020). Social capital at different levels and dimensions: A typology of social capital. Social Capital Research, 1-10.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95-S120.

Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Harvard University Press.

Crook, C. J. (1997). Cultural practices and socioeconomic attainment: The Australian experience. Greenwood Press

Darcy, S., Maxwell, H., Edwards, M., Onyx, J., & Sherker, S. (2014). More than a sport and volunteer organisation: Investigating social capital development in a sporting organisation. Sport Management Review, 17(4), 395-406.

Dasgupta, P. (2005). Economics of social capital. Economic Record, 81, S2-S21.

Foley, M. W., & Edwards, B. (1999). Is It Time to Disinvest in Social Capital? Journal of Public Policy, 19(2), 141–173.

Fraser, E., & Lacey, N. (1993). The Politics of Community: A feminist critique of the liberal-communitarian debate. University of Toronto Press.

Goldtborpe, J. H. (1996). The quantitative analysis of large-scale data-sets and rational action theory: For a sociological alliance. European Sociological Review, 12(2), 109-126.

Glaeser, E. L., Laibson, D., & Sacerdote, B. (2002). An economic approach to social capital. The Economic Journal, 112(483), F437-F458.

Glicksman, A., Ring, L., & Kleban, M. H. (2016). Defining a framework for age-friendly interventions. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 30(2), 175-184.

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360-1380.

Greenberg, Z., Cohen, A., & Mosek, A. (2016). Creating community partnership as foundation for community building: The case of the renewed Kibbutz. Journal of Community Practice, 24(3), 283-301.

Grootaert, C. (1998). Social capital: The missing link (English). Social Capital Initiative Working Paper Series No. 3. The World Bank.

Grootaert, C., Narayan, D., Jones, V N., & Woolcock, M. (2004). Measuring social capital: An integrated questionnaire. World Bank Publications.

Halstead, J. M., Deller, S. C., & Leyden, K. M. (2022). Social capital and community development: Where do we go from here? Community Development, 53(1), 92-108.

Hanibuchi, T., Kondo, K., Nakaya, T., Shirai, K., Hirai, H., & Kawachi, I. (2012). Does walkable mean sociable? Neighborhood determinants of social capital among older adults in Japan. Health & Place, 18(2), 229-239.

Hanibuchi, T., & Nakaya, T. (2013). Contextual determinants of community social capital. In I. Kawachi, S. Takao, & S. V. Subramanian (Eds.), Global perspectives on social capital and health (pp. 123-142). Springer.

Häuberer, J. (2011). Social capital theory: Towards a methodological foundation. Wiesbaden.

Hawes, D. P., & Rocha, R. R. (2011). Social capital, racial diversity, and equity: Evaluating the determinants of equity in the United States. Political Research Quarterly, 64(4), 924-937.

Jenkins, R. (1992). Pierre Bourdieu. Routledge.

Kaasa, A. (2019). Determinants of individual-level social capital: Culture and personal values. Journal of International Studies, 12(1), 9-32.

Kaasa, A., & Parts, E. (2008). Individual-level determinants of social capital in Europe: Differences between country groups. Acta Sociologica, 51(2), 145-168.

Kawachi, I., Subramanian, S. V., & Kim, D. (Eds.). (2007). Social capital and health. Springer.

Krasny, M. E., Kalbacker, L., Stedman, R. C., & Russ, A. (2015). Measuring social capital among youth: Applications in environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 21(1), 1-23.

Lin, N. (2001a). Building a network theory of social capital. In N. Lin, K. Cook, & R. S. Burt (Eds.), Social capital theory and research (pp. 3-30). Aldine De Gruyter.

Lin, N. (2001b). Social capital: A theory of social structure and action. Cambridge University Press.

Lin, N. (2008). A network theory of social capital. In D. Castiglione, J. van Deth, & G. Wolleb (Eds.), The handbook of social capital (pp. 50-69). Oxford University Press.

Lindström, M., Merlo, J., & Östergren, P. O. (2002). Individual and neighbourhood determinants of social participation and social capital: A multilevel analysis of the city of Malmö, Sweden. Social Science & Medicine, 54(12), 1779-1791.

Molyneux, M. (2002). Gender and the silences of social capital: Lessons from Latin America. Development and Change, 33(2), 167-188.

Onyx, J., & Bullen, P. (2000). Measuring social capital in five communities. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 36(1), 23-42.

Onyx, J., & Bullen, P. (2001). The different faces of social capital in NSW Australia. In P. Dekker, & E. M. Uslaner (Eds.), Social capital and participation in everyday life (pp. 45-58). Routledge.

Pitas, N., & Ehmer, C. (2020). Social Capital in the Response to COVID-19. American Journal of Health Promotion, 34(8), 942-944.

Portes, A. (1998). Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 24, 1-24.

Putnam, R. (1993a). The prosperous community: Social capital and public life. The American Prospect, 13(Spring), 35-42.

Putnam, R. (1993b). Making democracy work: Civil traditions in modern Italy. Princeton University Press.

Putnam, R. (1995). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6(1), 65–78.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon & Schuster.

Rapeli, M. (2018). Social capital in social work disaster preparedness plans: The case of Finland. International Social Work, 61(6), 1054-1066.

Roxas, H. B., & Azmat, F. (2014). Community social capital and entrepreneurship: Analyzing the links. Community Development, 45(2), 135-150.

Schuller, T. (2001). The complementary roles of human and social capital. Canadian Journal of Policy Research, 2(1), 18-24.

Siisiäinen, M. (2000, July 5-8). Two concepts of social capital: Bourdieu vs Putnam [Paper presentation]. ISTR Fourth International Conference, Dublin, Ireland.

Su, F., Song, N., Shang, H., Wang, J., & Xue, B. (2021). Effects of social capital, risk perception and awareness on environmental protection behavior. Ecosystem Health and Sustainability, 7(1), 1942996.

Swain, N. (2003). Social Capital and its uses. European Journal of Sociology, 44(2), 185–212.

Tonkiss, F. (2000). Trust, social capital and economy, In F. Tonkiss, A. Passey, N. Fenton & L. C. Hems (Eds.), Trust and Civil Society. MacMillan Press Ltd.

United Nations Development Programme. (2009). The ties that bind: Social capital in Bosnia and Herzegovina. National Human Development Report 2009.

Uslaner, E.M. (2002). The moral foundation of trust. Cambridge University Press.

Van Oorschot, W., Arts, W., & Gelissen, J. (2006). Social capital in Europe: Measurement and social and regional distribution of a multifaceted phenomenon. Acta Sociologica, 49(2), 149-167.

Villalonga-Olives, E., Wind, T. R., & Kawachi, I. (2018). Social capital interventions in public health: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 212, 203-218.

Wallis, J., Killerby, P., & Dollery, B. (2004). Social economics and social capital. International Journal of Social Economics, 31(3), 239-258.

Walters, W. (2002). Social capital and political sociology: Re-imagining politics? Sociology, 36(2), 377-397.

Williams, T., McCall, J., Berner, M., & Brown-Graham, A. (2022). Beyond bridging and bonding: The role of social capital in organizations. Community Development Journal, 57(4), 769-792.

Woolcock, M. (1998). Social capital and economic development: Toward a theoretical synthesis and policy framework. Theory and Society, 27(2), 151-208.

Woolcock, M. (2001). The place of social capital in understanding social and economic outcomes. Canadian Journal of Policy Research, 2(1), 11-17.

Woolcock, M., & Narayan, D. (2000). Social capital: Implications for development theory, research, and policy. The World Bank Research Observer, 15(2), 225-49.

Zhang, Y., Zhou, X., & Lei, W. (2017). Social capital and its contingent value in poverty reduction: Evidence from Western China. World Development, 93, 350-361.