Section One: Introduction to Social Capital Theory

Major Theories of Social Capital

In academia, renowned scholars of social capital theory mainly include Pierre Bourdieu, James Coleman, Robert Putnam, and Nan Lin. The research scope of Pierre Bourdieu, James Coleman, and Nan Lin primarily focuses on individual-level social capital, while Robert Putnam approaches the concept from the societal perspective. However, all four scholars' theories highlight the interrelations between individual and societal levels.

Pierre Bourdieu's Theory: Theory of Capital

Pierre Bourdieu's (1977, 1986, 1990) main area of research focuses on the reproduction of social class, status, and power relations, involving three forms of capital: economic, cultural, and social capital. In Bourdieu's view, class reproduction can be explained not only through economics but also social class interactions (i.e., social capital) and the process of transmitting cultural knowledge (i.e., cultural capital) (Bourdieu, 1986; Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992).

According to Bourdieu, social capital is the aggregate of actual or potential resources linked to the possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalised relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition (Bourdieu, 1986, p. 249). Bourdieu points out that the levels of social capital an individual possesses depend on the size of the network they can effectively mobilise and their economic or cultural capital levels (Bourdieu, 1986). Bourdieu (1984) also indicates that cultural capital is distributed differently among various groups and directly related to class differences. Bourdieu (1977, 1986, 1990) and Crook (1997) both state that education can influence cultural practices, enabling different classes to acquire various types and levels of cultural capital through formal and informal education (e.g., parental teaching). For example, university students may have more opportunities to learn classical music; the dominant class can pass on their cultural capital (e.g., sophisticated manners and lifestyles) to their children. Through the transmission of this cultural capital, social class relationships (i.e., social capital) are reproduced, and their economic capital is maintained.

Some scholars (Alexander, 1996; Jenkins, 1992) opine that Bourdieu's theory is reductionism, as it views economic capital as the ultimate source and exchange form of all other types of capital. Goldthorpe (1996) also points out that Bourdieu attributes all human behaviour to interest relations. Schuller (2001, p. 12) notes that this orientation has limitations, because from this perspective, accumulating social capital ultimately leads to social stratification and inequality.

James Coleman's Theory: Rational Choice

Like Bourdieu, James Coleman (Coleman, 1988, 1990) also views social capital as a personal asset and a collective resource. However, unlike Bourdieu, Coleman considers social capital a pattern of social structure that facilitates individual activities in specific contexts to gain benefits (Coleman, 1990). To benefit from activities, people would interact with each other, exchanging and transferring resources. These social interactions form the foundation of social capital.

Additionally, social capital is productive with a clear instrumental purpose, meaning that individuals can use social capital to achieve specific goals. Hence, social capital necessarily exists in society and is embedded within social structures. As Coleman states, social capital refers to the resources within the structure of social relationships, including interpersonal relationships and institutional connections (such as family, school, work, and community environments). Through these interactive social relationships or networks, people acquire various political and economic information and resources to enhance their socioeconomic status. Therefore, individuals with more social networks tend to have a higher socioeconomic status. However, unlike Bourdieu, Coleman regards social capital as a bonding mechanism that connects people, facilitating social structure integration (Coleman, 1988, 1990).

Coleman also points out that social capital is regarded as a public good, meaning that an individual's contributions within network relationships (such as family or community relations) can benefit the overall society/group (Coleman, 1988, 1990). However, as many scholars (Fraser & Lacey, 1993; Molyneux, 2002; Tonkiss, 2000) note, Coleman pays less attention to analysing social capital regarding structural inequality and power relations.

Robert Putnam's Social Capital Theory: Civic Perspective

Robert Putnam (Putnam, 1993a, 1995, 2000) adopts the theoretical principles proposed by Coleman and expanded them to analyse social capital from a political science perspective. In his view, social capital refers to "features of social organisation such as networks, norms, and trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit" (Putnam, 1993a, p. 35). Putnam believes that social capital is an element that can promote interpersonal cooperation, and he uses voluntary associations in democratic societies as an example to illustrate the application of his theories. He considers that voluntary associations represent civil engagement, which can promote and enhance norms and trust among people within the group, ultimately generating and maintaining collective well-being (Putnam, 1993a, 1995).

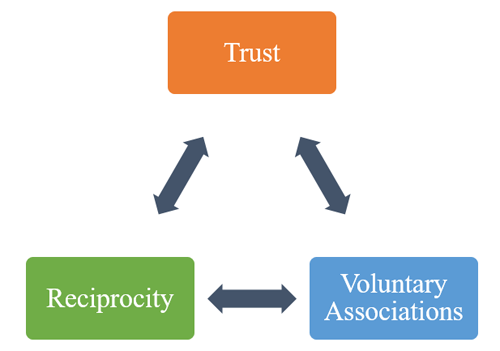

Based on Putnam’s viewpoint, voluntary associations promote horizontal connections between people and generate trust. This trust leads to reciprocity, social networks, and the development of voluntary associations, forming the foundation of social capital. There is a cycle among trust, reciprocity, and voluntary associations: trust generates reciprocity and voluntary associations; the strengthening of reciprocity and voluntary associations also generates trust (Putnam, 1993b, pp. 163-185) (Figure 3). At the same time, Putnam particularly links trust, reciprocity and civic engagement, using this as an index of the strength of civil society. In short, social capital is closely related to social participation (primarily through social participation in voluntary associations). Therefore, Putnam believes that social capital is a direct measure of civic strength and can serve as a tool reflecting social, political, and economic prosperity (Putnam, 1993a, 1995, 2000). However, some scholars (Portes, 1998; Brucker, 1999; Foley & Edwards, 1999; Swain, 2003) consider that Putnam has not accurately analysed the causal relationship between social capital and social, political, and economic prosperity. Furthermore, Putnam has not discussed the conflicts and internal power structures between political parties and voluntary associations or the contradictions between civil society and political society (and the state) (Siisiäinen, 2000).

Nan Lin's Social Capital Theory: Network Approach

Nan Lin's (Lin, 2001a, 2001b) theory primarily focuses on relational assets. He points out that social capital originates within social networks and relationships (Figure 4). Lin (Lin, 2001a, p. 12) defines social capital as "resources embedded in a social structure that are accessed and/or mobilised in purposive actions". Lin's definition of social capital includes three elements: (1) resources that are embedded in social structures, (2) the accessibility of these social resources, and (3) their application in purposive actions. Lin further proposes that effectively utilising social resources within social networks can enhance social and economic status; at the same time, the (partial) use of social resources depends on socioeconomic status and the utilisation of social networks.

Unlike the other three scholars, Nan Lin extends the discussion of social capital to open social networks (Lin, 2001a). He notes that the effectiveness of closed social networks (also known as strong ties) lies in maintaining individuals' resources and cooperation. In contrast, the utility of open social networks (also known as weak ties) is in facilitating the increase of resources and the execution of purposive actions (Lin, 2008). Later, Lin (2008) also mentions social capital at the collective level, indicating that internal social capital within a group derives from the resources provided by its members, effectively maintaining the unity and cohesion of the group. External social capital, on the other hand, refers to resources and networks outside the group obtained by linking with other groups and organisations, but its effectiveness depends on the connections and openness between different groups. Nevertheless, some scholars points that Lin did not thoroughly explore the potential of using social capital to address social inequality (Häuberer, 2011).

Back to Table of Contents Page 1 2 3 4 5 6 References